Pain perception and psychology are linked. As with the chicken-and-the-egg scenario, a question arises: what comes first?

- Does an abnormal psychological profile cause chronic pain?

Or

- Does chronic pain cause an abnormal psychological profile?

The relationship between the link of pain perception and psychology is particularly important in cases where compensation is involved. It is known that pain afferents fire to the limbic system, affecting one’s emotions and psychological profile (1).

The source of chronic cervical spinal pain, as a rule, is multimodal (2). In 2011, Dr. Nikolai list six:

- Intra-articular Hemorrhage

- Facet Capsular Tear

- Meniscoid Contusion

- Articular Subchondral Fracture

- Fracture of the Articular Pillar

- Disc Tear or Torn From the Vertebral Rim

In 1993, Nikolai Bogduk, MD, PhD, and Charles Aprill, MD (3) were able to show that in 23% of individuals who were suffering from chronic post-traumatic neck pain, the tissue source for the pain was a single cervical zygapophysial (facet) joint. This finding is important because such individuals are ideal for evaluating the relationship between pain and psychology. This finding allowed the research team that includes Barbara Wallis, Susan Lord PhD, and Nikolai Bogduk MD, PhD to investigate the relationship between whiplash pain psychology and organic whiplash pain (4). Their 1997 study was published in the journal Pain, and titled (4):

Resolution of psychological distress of whiplash patients following treatment by radiofrequency neurotomy:

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial

The author’s goal was to determine between:

- The psychological model of chronic neck pain following whiplash: whether psychological distress precedes and causes the chronic pain.

or

- The medical model: whether the psychological distress is a consequence of chronic pain.

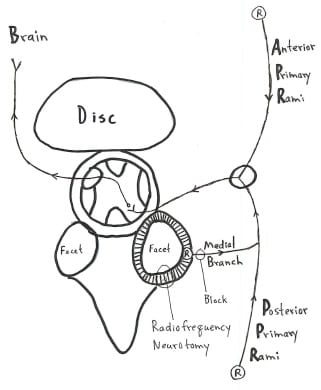

The authors used the SCL-90-R psychological profile, the McGill Pain Questionnaire, and the visual analogue pain scale to evaluate 17 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled patients with a single painful cervical zygapophyseal joint, using percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy. These 17 patients were found to have a single painful zygapophyseal joint diagnosed by double-blind, placebo-controlled cervical medial branch blocks of the posterior primary rami. The placebo group received the same invasive procedure, but no radiofrequency current was delivered.

These authors note:

- There is little evidence of useful clinical improvement following psychological treatment in these chronic whiplash pain patients. “Even when psychological improvement has been demonstrated, it has not been associated with clinically useful degree of pain reduction, let alone complete relief of pain. At best, psychological interventions enable patients to return to work in spite of their pain.”

- Percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy is a 3-hour, local anesthetic, operative neuroablative procedure which provides long-term, complete pain relief by coagulating the nerves that innervate the painful zygapophyseal joint. This neurosurgical procedure has been validated in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study.

- Radiofrequency neurotomy does not effect a permanent cure. It provides long-term analgesia (months to years). Recurrence of the pain is natural as the coagulated nerve heals.

The results of this study were:

- At 3-months post-operative assessment, all patients who were pain free exhibited resolution of psychological distress. In contrast, only one patient whose pain was present at 3-month assessment exhibited improvement in her level of psychological distress. “The association between complete relief of pain and resolution of psychological distress was very strong.”

- “As their original pain recurred, so did their psychological distress, but when successful active neurosurgical treatment again achieved pain relief, the psychological distress was again resolved.”

- “None of the patients received any formal psychological therapy. The only intervention was the operative procedure. Therefore, such changes in the psychological profile as were observed can only be ascribed to the neurosurgical intervention.”

- The results of this study clearly refute the psychological model, which would have predicted that because no psychological intervention was administered, no patient should have exhibited improvement in either their pain or psychological status. “Yet, ten patients exhibited complete resolution of psychological distress.”

These authors concluded:

“This result calls into question the present nihilism about chronic pain, that proclaims medical therapy alone to be ineffectual, and psychological co-therapy to be imperative.”

“All patients who obtained complete pain relief exhibited resolution of their pre-operative psychological distress. In contrast, all but one of the patients whose pain remained unrelieved continued to suffer from psychological distress. Because psychological distress resolved following a neurosurgical treatment which completely relieved pain, without psychological co-therapy, it is concluded that the psychological distress exhibited by these patients was a consequence of the chronic somatic pain.”

••••

Reverse causality refers to a direction of cause-and-effect contrary to a common presumption. Reverse causality is cause and effect in reverse. That is to say the effects precede the cause. The problem is when the assumption is A causes B when the truth may actually be that B causes A.

It is often stated in published studies, by insurance companies, and by their representatives (lawyers, claims adjusters, IME doctors, etc.) that injured patients who seek compensation (ask for compensation, hire a lawyer, etc.)(A), have worse health outcomes and slower recovery rates (B).

However, such adverse health outcomes do not consider or evaluate the concept of Reverse Causality: “slower recovery (B) leads individuals to claim, seek legal advice, and litigate (A).”

In my experience, which is extensive, many injured people feel compelled to seek legal counsel because it is their belief that their insurance company is treating them unfairly, hindering them from obtaining the treatment they need to recover.

••••

The contemporary leaders in the research pertaining to injury compensation, health outcomes, and Reverse Causality is Natalie Spearing and colleagues from the University of Queensland in Australia. In 2011, Natalie Spearing and Luke Connelly published a study in the journal Injury, titled (5):

Is compensation “bad for health”?

A systematic meta-review

These authors performed a systematic meta-review (a “review of reviews”) on this topic, which constituted the most comprehensive review pertaining to compensation and health outcomes through the publication date. Their conclusions include:

“There is a common perception that injury compensation has a negative impact on health status among those with verifiable and non-verifiable injuries, and systematic reviews supporting this thesis have been used to influence policy and practice. However, such reviews are of varying quality and present conflicting conclusions.”

“Systematic reviews that have sought to examine the link between compensation and health outcomes are subject to the inherent methodological weaknesses of observational studies and many do not evaluate the quality of the studies that comprise the dataset for their analysis. Moreover, the extant approaches to health outcomes measurement in this literature may bear a dubious relation to the latent health state of interest, and their use is not validated.”

“There is evidence from one well-conducted systematic review (focusing on one legal process and on health outcome measures) of no association between litigation and poor health outcomes among people with whiplash, contradicting the hypothesis that such an approach contributes to poorer health status.” (6)

The contention that “compensation is ‘bad for health’, should be viewed with caution.”

These authors used 11 studies that met their stringent inclusion criteria. Nine of the 11 reviews concluded that health outcomes are poorer among people seeking or receiving compensation compared to uncompensated individuals. However, all 9 of them were of low quality and suffered from a number of methodological flaws.

In contrast, one review, the Scholten-Peeters (6) study, concluded there is no evidence of an association between compensation and health outcomes. This study was judged by the authors to be the highest quality study in their review. It was published in the journal Pain in 2003.

The studies presented in this review were published in the best journals over a period of decades. Based upon these studies, it can be said:

- Studies that claim that those suffering from chronic problems following whiplash injury do so in hope of gaining financial compensation have methodological flaws.

- The best methodologically done studies show there is no association between litigation/compensation and recovery from whiplash injury.

- Individuals suffering from chronic whiplash injuries do exhibit an abnormal psychological profile. However, their abnormal psychological profile is consistent with the abnormal psychological profile of those who are suffering from other types of organically based chronic pain syndromes.

- Smart individuals attempting to obtain financial compensation are unable to fake the psychological profile of a true chronic pain whiplash sufferer.

- Psychotherapy has not been shown to be effective in treating chronic whiplash pain. This does not undervalue psychotherapy for the treatment of other aspects of whiplash trauma, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, etc.

- Successful treatment of a whiplash patient’s chronic pain normalizes their psychological profile.

- The abnormal psychological profile of chronic whiplash patients is secondary to the chronic pain.

- It is wrong to claim that chronic whiplash symptoms are primarily the consequence of litigation and desire for monetary gain.

••••

This year (2012), Natalie Spearing and colleagues published another on-topic study in the journal Pain, titled (7):

Does injury compensation lead to worse health after whiplash?

A systematic review

In this study, the authors note that the assessment of the relationship between compensation and health outcomes are bogus if that study used “proxy” measures for health. Such an example would include that claiming people’s heath had recovered if that person is able to return to work. Logic and clinical experience notes that such an approach is flawed because clinicians often have injured patients return to work before their clinical syndrome is completely resolved. In fact, often patients miss no work at all while under treatment, yet under these proxy criteria they are considered to be uninjured. One such proxy study (the authors note) is authored by chiropractor David Cassidy and colleagues and published in the New England Journal of Medicine (8).

In this article, Spearing and colleagues introduce the concept of Reverse Causality Bias in the evaluation of the relationship between compensation and health outcome. They note that Reverse Causality Bias occurs when the results of a study are interpreted to mean that whiplash-injured people who hire lawyers to obtain compensation have worse health recovery outcomes; when in fact it may actually mean that whiplash-injured people with greater injuries, more pain and more disability are the ones who seek lawyers to help them obtain the benefits they need.

This study systematically reviewed the evidence on the ‘‘compensation hypothesis’’ using PubMed, CINAHL, EMBASE, PEDro, PsycInfo, CCTR, Lexis, and EconLit. The authors note that many believe that compensation after whiplash injury does more harm than good. There is a view that injury compensation leads to worse health; this is called the “compensation hypothesis.” This view that compensation is harmful has been used to argue for reductions to compensation benefits, to influence judicial decisions, and to advise people that compensation payments will impede their recovery.

Nine of 16 studies used in this review (56%) indicated that compensation adversely influenced health outcomes. However, none evaluated or considered the potential for Reverse Causality Bias in making their conclusions. “Consequently, there is no clear evidence to support the idea that compensation and its related processes lead to worse health.” These authors state:

“It is not possible to tell if statistically significant negative associations reflect a ‘compensation effect,’ or if they simply reflect the pursuit of compensation by those with comparatively worse health and/or a worse prognosis (a selection effect); however, the former is often assumed.”

“Our overall conclusion, that it is currently not possible to determine whether or not compensation leads to worse health after whiplash because reverse causality bias has not been addressed, varies from that of earlier systematic reviews on whiplash as they did not consider this source of bias.”

Claiming “lawyer involvement leads to worse pain,” could also be interpreted as “worse pain increases the likelihood of lawyer involvement.”

“The potential for reverse causality bias is largely unacknowledged in the whiplash literature, and lies similarly unaddressed in studies on other types of compensable injuries.”

“It is important to ascertain whether statistically significant negative associations between compensation-related factors and health do indeed indicate that exposure to these factors leads to worse health, or whether they simply reflect the likelihood that people in comparatively worse health (eg, pain) are more likely to pursue compensation. Unless the latter possibility is considered, decisions to reduce compensation benefits, for example, may inadvertently disadvantage those who are in most need of assistance, which would be an undesirable (and unintended) policy consequence.”

“Only when reverse causality is addressed will it be possible to make well-informed and fair decisions about injury compensation benefits, schemes, and related processes.”

“Research in this field has important implications for the design of injury compensation schemes and the health and well-being of injured people. It is important to raise awareness of the limitations of the existing evidence to avoid ineffectual and potentially harmful policy and judicial decisions.”

••••

Last month (November, 2012), Natalie Spearing and colleagues extended their research on these topics with a study published in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, titled (9):

Research on injury compensation and health outcomes:

Ignoring the problem of reverse causality led to a biased conclusion

This study highlights the serious consequences of ignoring Reverse Causality Bias in studies on compensation-related factors and health outcomes. These authors evaluated Reverse Causality using a sophisticated, ingenious, evaluation of compensation claims associated with recovery from neck pain (whiplash) after rear-end collisions. The analysis offered by these authors is extremely mathematical. They note that the standard method used to declare “compensation negatively affects recovery” uses a “standard single equation approach.” However, to assess “reverse causality”, a “simultaneous equation technique” must be used. When the “simultaneous equation technique” is used, the results “tell a different story.”

This study used a source population of 1,174 adults with injuries arising from a rear-end vehicle collision. Of these, 503 agreed to participate in the study. Eighty percent (403/503) developed neck pain within 7 days of collision (early whiplash); 20% (100/503) developed neck pain after 7 days of collision. Sixty-five percent of those with early whiplash symptoms became claimants (265/403), while 35% of those with early whiplash symptoms were non-claimants (138/403). Neck pain at 24 months was selected as the primary health outcome. Neck pain severity was measured using the visual analogue scale (VAS) score (0–100). Higher VAS scores indicate worse pain: a score of 100 represents the worst pain imaginable and zero represents no pain.

These authors state:

“Although it is commonly believed that claiming compensation leads to worse recovery, it is also possible that poor recovery may lead to compensation claims—a point that is seldom considered and never addressed empirically.”

“When reverse causality is ignored, claimants appear to have a worse recovery than non-claimants; however, when reverse causality bias is addressed, claiming compensation appears to have a beneficial effect on recovery.”

Reverse Causality must be evaluated to “avert biased policy and judicial decisions that might inadvertently disadvantage people with compensable injuries.”

“There is a prevailing belief that compensation does more harm than good, and this idea—that claimants are worse off— influences decisions about injury compensation laws.”

An assumed belief is that the lure of compensation prompts individuals to exaggerate subjective symptoms. But, “no studies have examined the effect of compensation payments per se on health.”

In assessing injury outcomes, “reverse causality must also be considered because the causal relationship between compensation factors and health is ambiguous.” “Claiming compensation, lawyer involvement, and litigation, may lead to slower recovery, but it is also possible that slower recovery leads individuals to claim, seek legal advice, and litigate.”

“The consequences for statistical inference of ignoring reverse causality bias are potentially serious: if negative associations between compensation-related factors and health status actually reflect worse health among those pursuing compensation (a rarely considered, but entirely plausible proposition), then decisions to limit access to compensation benefits may do more harm than good.”

“Once reverse causality bias is addressed, people who claim compensation appear to experience a better recovery from neck pain at 24 months compared with non-claimants.”

“The results of this study suggest that compensation claiming may not be disadvantageous to injured parties after all and that it may even have a beneficial effect,” because access to financial assistance and/or treatment may “indeed relieve pain and suffering. This is, after all, one of the motivations for compensating people who have sustained an insult to their health.”

“Neck pain is significantly worse at baseline among claimants compared with non-claimants, which suggests that claims are more likely to be made by individuals whose initial neck pain is worse.”

Reverse causality “is largely overlooked in studies on compensation-related factors.” Yet, this study shows that people with worse health tend to claim compensation.

Policies that restrict access to compensation benefits or legal advice may inadvertently disadvantage people who need financial or legal assistance.

“This study serves as a reminder of the dangers of drawing causal interpretations from statistical associations when the causal framework is ambiguous. It establishes, empirically, that reverse causality must be addressed in studies on compensation-related factors and health outcomes.”

These authors reject the hypothesis that the decision to claim compensation negatively affects recovery.

•••••••••

SUMMARY:

This review reminds us that it is well established that:

- Whiplash injury chronic pain is primarily generated by injury to the facet joint capsular ligaments.

- Facet joint capsular chronic pain can cause an abnormal psychological profile.

- The abnormal psychological profile caused by chronic facet pain can only be successfully treated if the chronic pain is successfully treated.

- Many studies conclude that litigation (hiring a lawyer) subsequent to an injury is “harmful to recovery.” However, these studies do not evaluate the concept of Reverse Causality, and hence are flawed.

- When Reverse Causality is carefully evaluated, litigation not only does not harm recovery, data suggests it actually improves recovery.

REFERENCES

- Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM; Principles of Neural Science, Elsevier; 2000.

- Bogduk N; On Cervical Zygapophysial Joint Pain After Whiplash; Spine December 1, 2011; Volume 36, Number 25S, pp. S194–S199.

- Bogduk N, Aprill C; On the nature of neck pain, discography and cervical zygapophysial joint blocks; Pain; 54; 1993, pp. 213-217.

- Wallis, BJ, Lord, SM and Bogduk, N (1997). “Resolution of psychological distress of whiplash patients following treatment by radiofrequency neurotomy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.” Pain; 73: pp. 15-22.

- Spearing NM, Connelly LB; Is compensation “bad for health”? A systematic meta-review; Injury; January 2011; Vol. 42; No. 1; pp. 15-24.

- Scholten-Peeters GGM, Verhagen AP, Bekkering GE, van der Windt DAWM, Barnsley L, Oostendorp RAB, Hendriks EJM; Prognostic factors of whiplash-associated disorders: A systematic review of prospective cohort studies; Pain ; July 2003, Vol. 104, pp. 303–322.

- Spearing NM, Connelly LB, Gargett S, Sterling M; Does injury compensation lead to worse health after whiplash? A systematic review; Pain; June 2012; 153; No. 6; pp.1274-82.

- Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Côté P, Lemstra M, Berglund A, Åke Nygren A; Effect of Eliminating Compensation for Pain and Suffering on the Outcome of Insurance Claims for Whiplash Injury; New England Journal of Medicine; April 20, 2000; Vol. 342; No. 16; pp. 1179-1186.

- Spearing NM, Connelly LB, Nghiem HS, Pobereskin L; Journal of Clinical Epidemiology; November 2012; Vol. 65; No. 11; pp. 1219-1226.